Human rights, a vague declaratory term that provides no insight as to where they come from. While the concept of human rights or individual rights originated from the natural rights, both concepts are now ruled by the zealous rationale of egalitarianism and freedom. Egalitarianism asserts that individuals have rights to abortion, rights to healthcare, rights to food, rights to a shelter, rights to equal pay, etc. These alleged rights can be derived from any number of books, theories, beliefs, religious doctrine or logical backflips. This paper is going to explore the shifting of the American political society from pursuing the common good to the desire for individual rights as moral objectivity was replaced by the pseudo-religious conception of egalitarianism under the grand umbrella of moral relativism which has displaced the social contract, with social demands.

While there are few distinctions between rights that can be made[1], for the sake of this paper the difference between natural rights, fundamental positive rights and ordinary positive rights will be the primary focus once the ground upon which the concepts of American rights has been shown.

Preview

The essay will first give a definition of the term freedom, equality, and right, that will have a functional use within the narrower categories of rights. Then the differences between natural and positive rights will briefly be touched upon as to lay the foundation for the Social Contract Theory and its conceptual background in the modern era. After which, the goal of a political society will be discussed as the common good. This will bring up the lack of an ethos by which a common goal can be defined. Finally, resulting in the showing that individual rights are contradiction to a common good as egalitarianism is all about the self.

- Definitions and Terms

As with any reasonable endeavor to further one’s understanding of a concept or any topic substantively. The definitions of words and terms used in the study of the topic are of vital importance. Further, the definitions of conceptual words are of consequence in order to grasp a topic or even have a discussion about a topic, as the proverbial saying goes: there can be no reason when the definitions of the words being used are not agreed upon.[2] Much of the language used to convey these ideas are old and have been re-salvaged several times for different religious, cultural, political and social means.

Prior to getting into the differences between natural, positive, and negative rights. The terms freedom, equality and right need to be defined.

- Freedom: The Mythical Beast of Fantasy.

The term Freedom has scientific, philosophical, legal, as well as everyday uses. Freedom is one of the most butchered words of the 20th and 21st centuries. The way it is so loosely used to describe the willy nilly desires of anyone and everyone who invokes its name is disgusting from a reasonable, conceptual, and linguistic perspective. The word comes from the Freo which means “to love” like love which is beyond just having a feeling for something there is a tradeoff. Freo can also mean to share with a friend, as anyone who knows about friendship there is a give and take necessary to keep friendships healthy.

In the more modern ages the term Free, has meant not a slave, not subject to foreign domination nor a despotic government. All to say that one was released from the physical bounds that previously restricted them. However, the concept of being “free” to do whatever one wants to do subtly snuck into the common use of the term freedom in the 19th and 20th century.

The way the term “free” was used for most of its usage was in contrast be being forced into living a lifestyle that one did not have a choice in and was outside of the person’s control. Whereas freedom historical meant that the decisions that one was making with their life were independent of the coercive force of a master, lord, aristocrat or monarch. However, the idea of freedom expanded to mean that one should be able to do whatever they want to do, and that certain acts, behaviors and lifestyles should be acceptable was never a fore or afterthought when the term free(dom) was being uttered prior to the 19th century, or when it was used in the Declaration of Independence, or any of the United States Founding Documents. Thereby, freedom in the modern era is a political principle, which is merely a buzzword used along rights to justify an individual’s actions outside the content of the common good.

- Equality, Equity, and The Fairytale of Egalitarianism:

Equity comes from equal which the Latin is aequus which is commonly derived from the use of “being flat,” “even” or “level.” But the term Equity in its modern definition seems closer to the word superaequum when as a noun it is “over the plain” and when used as an adjective it can mean “razed,” as in the land was razed to level it out. Equity then is an attempt to “re-equalize outcomes” from between the separate already existing and newly defined groups.[3] Egalitarianism then requires one to notice that there are differences between individuals, but instead of accepting the differences between individuals, as innate or just, there must be an “unfair” structural order that set the differences up. Therefore, to achieve justice, the group or individual needs rights that assist that group in getting to the same level as a majority group or group member.

- What is a Right?

Upon a simple looking up of the term “right” one will see that it can refer to a physical direction, the correctness, or other abstract and conceptual meanings. Rights in the political and social realm tend to broadly refer to legal duties, obligations, and entitlements. Yet the scope of the term must be limited to have a meaningful discussion. When looking at the etymology of the word “Right”:

1. The word “right” originates from the Latin word Rēctus which can be translated as, straight, proper, or Righteous (moral integrity). Rectus is also the root word of the term Rectitude meaning morally correct behavior.[4]

2. “Old English riht (West Saxon, Kentish), reht (Anglian), “that which is morally right, duty, obligation,” also “rule of conduct; law of a land;” also “what someone deserves; a just claim, what is due, equitable treatment;” also “correctness, truth;” also “a legal entitlement (to possession of property, etc.), a privilege,” from Proto-Germanic *rehtan (see right (adj.1)).[5][6]”

For the sake of argument, the term Right or Rights in this paper shall mean an entitlement, since any rights argument is about what an individual inherently merits. The breadth of an entitlement is based on logic, beliefs, principles, and ideologies.

The problem with creating a simple and easy to understand definition for rights, is that similar to the right of Freedom of Speech one can go “round and round on the original meaning of the First Amendment”.[7] However, at the founding of United States the Founding Fathers believed in natural rights.[8][9] There is debate as to what specifically constituted natural rights during the Founding-Era. The Founding-Era being the period when both the Constitution, Bill of Right and Declaration of Independence were drafted, amended, and ultimately ratified (which is typically considered 1774 to 1797).[10] Nonetheless, what is ultimately agreed upon by scholars is that natural rights are rights that exist without government. Legal Scholar Jud Campbell in his Constitutional Commentary, Republicanism and Natural Rights at the Founding, argues that the natural rights considered in the Founding-Era were not legal privileges or Entitlements but a “mode of thinking” which would maintain a “good government, not necessarily less government.”[11] This idea of a good government ultimately is tied into the goal of any political society when it is founded, and is expressed via the common good.[12]

According to this perspective natural rights were philosophical pillars used by the Founding Fathers to apply to a social contract and create the Republican Government of the United States via the Constitution.[13] However, Campbell also posits that there were positive rights which required the Government to engage in certain forms of protections in exchange for control of the political society.[14]

- The Social Contract: Between Whom and Why?

Thomas Hobbes was the first modern Philosopher to assert The Social Contract Theory. In his book, Levithan, Hobbes lays out, through his version of first principles, how reason is a faculty of humans and that humans in the state of nature are inherently self-interested, though humans are self-interested they learn that though they cannot overcome nature they can reason with one another for cooperation which is the foundation of the social contract.[15] But just like nature imposes itself on humans, there needs to be someone, a Sovereign, at the top of the social contract that controls the tone of the people in a state.[16] The Sovereign is chosen because they have the ability, or power, to enforce the rules of the social contract when there are issues between individuals or if another state breaks the social contract that was maintained between ones state and another state.[17] However, in order for the social contract to be effective, the body of the state has to give up its individual rights to the Sovereign in order for him to maintain the desired order; Hobbes reasons that this is because individual persons’ ability to reason can be overrun by their passions, so the sovereign must have absolute control for the greater good of the body politic.[18]

John Locke was the second modern philosopher to speak about the Social Contract Theory. Locke outlines the state of nature and the laws of nature, suggesting that individuals in this period are still governed by moral principles; however, he acknowledges the potential for conflict and the need for government to protect individuals’ natural rights.[19] Consequently, for Locke, the purpose of government was the protection of property and the preservation of individuals natural rights against external and internal threats.[20][21] Locke emphasized that individuals enter into civil society and thereafter form a government to secure their natural rights, indicating the need for protection from others who would intrude on the enforcement of the right to self-preservation and a violation of an individuals right to self-preservation delegitimates a governments legislature.[22]

Thomas Jefferson, the primary Author of the Declaration of Independence[23] and James Madison, the primary Author of the Bill of Rights were both profoundly influenced by John Locke.[24] So much so that the term “pursuit of happiness” was lifted by Thomas Jefferson from one of John Locke’s writings[25] and in a correspondence with John Trumbull, Jefferson referred to John Locke as one of the greatest men who have ever lived;[26] Madison spoke of a government overreaching in their breadth and domain if they are attempting to decide or dictate what is “religious truth,”[27] which is nearly identical to Locke’s version in the “Letter on Tolerance”.[28] Over the centuries there has been challenges that have attempted to refute the influence that John Locke had on the American Revolutionaries[29] but in recent years the refutation has been completely dismantled.[30]

The Declaration of Independence makes four direct and indirect references to Natural Law: (1) “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights”. This statement implies that these rights are inherent to all individuals by virtue of their existence, aligning with the principles of natural law.[31] This was also seen as recognition of basic human rights.[32] (2) “That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed”. This suggests that the purpose of government is to protect natural rights, reflecting the concept of natural law as the foundation of legitimate governance, not that new rights are created via a new government but that the whole reason for government is to protect these naturally occurring rights;[33] (3) “That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it[,]” Here, the Declaration emphasizes the right of individuals to resist oppressive governments that violate natural rights principles;[34] and (4) “Appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions[,]” this reference acknowledges a higher moral authority, echoing the idea of natural law as a universal standard of justice.

The Bill of Rights refers to inalienable rights.[35] However, the founding documents of the United States were not merely a regurgitation of Lockean principles and treatises. Legal scholars have debated over what the American Social Contract constitutes as well as the effects of natural law on the social contract that was elected under the United States founding documents, yet there has been precedent in several states as well as Federal Courts of the social contract applying as a legal theory.[36]

- The Making of the Social Contract According to Jud Campbell

Campbell lays out four proposed stages of the social contracting completed in the Founding-Era:

- The first stage was recognizing that there are rights that exist outside the realm of any government, which would be natural rights. According to Zephaniah Swift who Published the first Legal Treatise in the United States,[37][38] natural law was “the enjoyment and exercise of a power to do as we think proper, without any other restraint than what results from the law of nature, or what may be denominated the moral law.”[39]

- The second stage was the negotiation stage where some of these natural rights were being discussed and an agreement as to the fundamental rights are being worked out, as the political society is figuring out where this line should be. [40]

- The third stage is where the Fundamental Positive Rights that a would-be Government must provide in exchange for the natural rights individuals relinquish for certain protects is established.[41]

- The fourth stage was after the political society, or government, is formed and ordinary positive rights are then created by the legislature, these ordinary positive rights are known by the common law and statutory rights that are ratified. This being a continuing event as the legislature ratifies and abolishes laws.

The relevance of these stages is important because in the modern day when it comes to certain alleged rights, the question arises whether they are natural rights that are protected by the social contract. Since at the third stage, it is assumed that individuals relinquish their natural rights in order to maintain the peace and security that is provided by a social contract.[42] This also implies that every individual consents to the political society, which results in a “single entity—a body politic—composed of all members of the political society.” [43] Campbell, while using the words of James Wilson[44] argues that “the first law of every government” is “the happiness of society”.[45] The Constitution[46] as well as the Federalist leader Theodore Sedgwick, felt that individuals rights could be suspended whenever said rights would “endanger ‘the public welfare.’”[47]

Campbell proceeds to explain Alexander Hamilton’s view that no rights were lost, and that federalist argued the same thing.[48] However, this was seen as a minority view, and contrary to what many of the founding fathers believed, articulated and wrote.[49] Campbell then asserts that the conflict regarding retained natural rights was largely a semantic one since it was commonly agreed that “the government could restrict natural liberty in the public interest.” Two of the common disagreements regarding natural rights being ones that explain the scope of the public interest. The first being: that natural rights were already part of social obligations so no rights were lost by political society controlling these rights for the social benefit of the group; and the second being: that natural liberty was preserved as the liberty was fairly traded for a representative political society. This latter assertion was foundational because “representative institutions could consent to restricts of natural liberty on behalf of individuals.”[50] Thereby, “the sovereignty of the society as vested in & exercisable by the majority, may do anything that could be rightfully done by the unanimous concurrence of the members.”[51]

Campbell then explains the difference between positive rights and fundamental rights and how they were not the same, but similar to the conception of fundamental positive rights and were combined; and how some of the founding fathers beliefs that enumerating the fundamental rights were not necessary since it was obvious; while others thought that even with rights enumerated there were other fundamental rights that could recognized.[52]

As the Founding Fathers “blamed the problems in the states under the Articles of Confederation on an excess of democracy,”[53] the idea of individual rights seems like a manipulation of founding documents towards egalitarian aims that were not envisioned in the founding-era. Further, James Madison questioned the impartiality of the common person to be able to have the interests of society, instead of their own. As Madison wrote “the great danger lies rather in the abuse of the community than in the legislative body”.[54] Madison appeared to be fearful of what a political society would look like when there was rule by popularity or even rule by the majority.[55] When discussing the issues regarding elected representatives Madison stated that most people sought public office because of their ambition and for self-interest, while few sought office for the sake of the public good.[56] Based on these observations, Madison believed that the biggest threat to the American Republic was factions that would seek that which would benefit their own faction but not what is good for every one within a society, because then factions will create coalitions with one another in order to benefit each other at the expense of other factions, not for the sake of the public good.[57] (This is what was originally coined with the aphorism The Tyranny of the Majority). Just to list a few observe the Caucasus we have today: Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus, Pacific Islands Caucus, Public Shipyard Caucus, Problem Solvers Caucus, New Democrat Coalition, Pro-Choice Caucus. Congressional LGBTQ+ Equality Caucus. Many of these Caucasus were not created solely for the common public good but merely for the good and interests of that group at the expense of others. Some will attempt to argue that “the assumption of a fixed-pie of resources” is the reason people believe that one group’s access to benefits is at the expense of another. However, as there are finite resources and a budget where there are only a set number of allocations possible. Yet, the larger point should not be missed that once a political society is separated by the interests of certain factions it means the common interests or goods are divergent from one another and not set towards the good of the whole political society, just certain constituents or Clienteles.

The shift from the rights that are necessary for the common good to the rights that benefit individuals appears to have happened in the early 19th century as industry and monopolies were granted special privileges and subsidies to establish a “more robust economy”. The libertarian idea of “a commitment to the public welfare to an interest in wealth accumulation” did not change from being a means of achieving the general welfare to being the end goal until the 1820’s.[58]

Currently, we have advocates for all sorts of new rights that were not around when the social contract was negotiated. There is a strong opinion that the social contract should be reaffirmed. There is also the opinion that every time a person votes they are reaffirming the social contract. The problem is that the common good, or the public interest is now inherently layered with self-interest, but further how is a consensus to be reached when there is not a common ethos in the United States. The ethos that is used to ratify laws or asserted positive rights appears to be via policy, principle, and the societal good.

- The Social Contract in Practice: The Battle Between Policy, Principle and the Societal Good.

Many scholars see an issue with public policy and how it has run amuck, as minority groups are receiving benefits that help their group at the expense of the common good. This statement can apply to schools of thought that fundamentally disagree with one another since terms like “minority,” and “common good” are buzzwords that can be plugged into many arguments regarding the way public policy is aimed. Such examples include wealthy persons, affirmative action, government housing, gender equality, desegregation, and oil subsidies. The same person who believes that a poor person, who cannot afford their housing or is homeless should receive housing from the government will also believe that is immoral for individuals with millions of dollars in assets to be able to use tax breaks. But both the poor and the wealthy are minorities. Within this category of believing the above statement to be true both Allan Bloom and Martha Nussbaum can be included, even though they fundamental disagree with each other as to how higher-educational institutions, governmental policy and philosophers should conduct themselves and influence the world.[59]

Appeals to public policy appear to be appeals to the vague way a policy sounds good, appeals to the emotional senses, or the vague notion of freedom. Such as providing tax breaks to blind people.[60] By contrast, Principles seem to justify a political decision that regulates or secures an individual right.[61] The argument for anti-discrimination statutes, comes from the principle of equality.[62] Public policy and principles are not mutually exclusive nor are other facial justifications, such as generosity or an ethical society excluded.[63]

While some scholars and philosophers such as John Rawls, who has influenced American public policy via his Original Position,[64] believed that the individuals rights should trump societal goals and should be the focus of public policy. In “A Theory of Justice” Rawls claims that “the rights secured by justice” are not beholden to “the calculus of social interests.”[65]

At the other end of the spectrum we have people like Ronald Dworkin, and Thomas Sowell who see an issue with “individuals rights [being] political trump cards held by individuals[,]” when the interests of society should be the ultimate goal.[66] Meanwhile, others argue that a balance should be struck between societal goals and human rights with a hierarchy displaying which should take priority and when.[67][68]

These positions of societal interest and individuals’ rights, both rely on public policy and Principles to appeal to the sense of the common good. But there is no longer a consensus as to ethos of the American morality. Some believe in objective morality and that is why their position should be upheld for the good of society, and others believe in relative morality which is why individual rights should be upheld more than anything else. This makes a differing vision between the common good, and its source of authority.

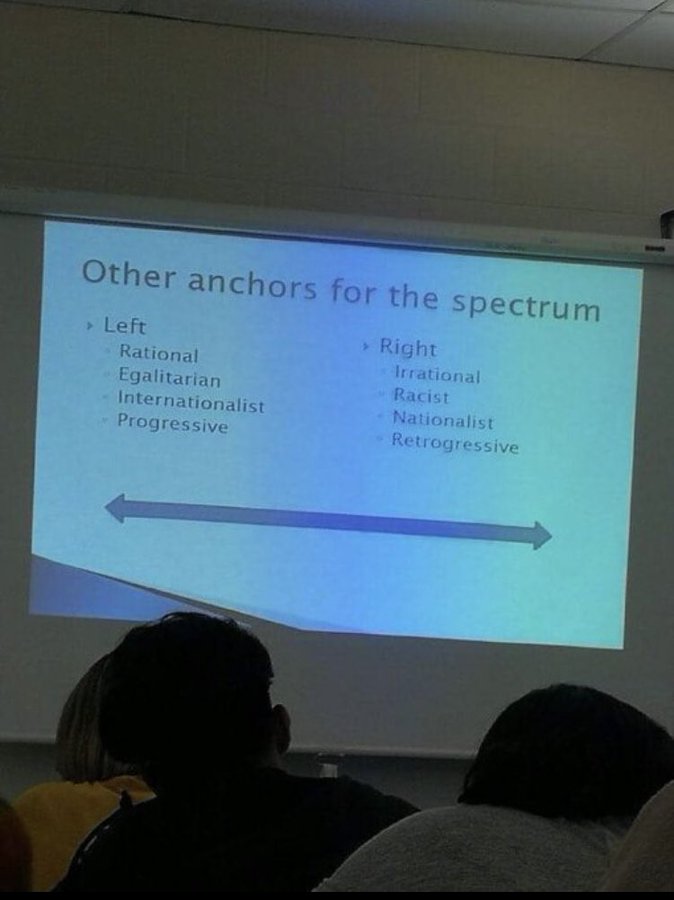

- The Warring Ethos: Objective Morality vs. Subjective Morality (aka nature versus egalitarianism)

We live in a fragmented political society, where there is no consensus as to the meaning of the societal good. There are scholars who believe that the United States is a Democracy, when the main drafter of the Constitution and Bill of Rights, James Madison, was vehemently against Democracy and wanted a Republic that consisted of a small number of representatives that sought the common societal good, not the rights of a group of people, or the rights of individuals to be championed.

Objective morality requires one to believe that there are actions that are good and that there are actions that are evil. However, the way one decides which action belongs to which category is dependent on the value system one subjects themselves to. In the Declaration of Independence, the phrase of “their Creator” is imbued with several connotations that legal and philosophers argue over, but the perspective that is clear is that this was meant as a matching Right by which to level Great Britain’s claim of superiority. Being as that most of the American colonials were at the very minimum deists, and the chief reason many decided to make the treacherous and deadly ocean voyage over the Atlantic was to get away from religious persecution dominated by the Protestants and Catholics. As these two groups were having violent battles within the nations themselves and between nations. Despite what was going on in Europe, there was peace, and space between these minority Christian denominations in the US. Thereby, Creator was a neutral term, which refers to God, without referring to a specific entity in the trinity or lack of trinity that was likely to cause strife within the American Settlers as they had complete contrasting views of the hierarchy within the church.

Accordingly, it follows that notions of being free were under the general view that there is a God or being that set the order to this world. While the first amendment makes it emphatic that there was to be no established religion the moral objectivity agreed upon by the United States founders, its elected representative, and appointed judges were also under the vague tutelage of an objective reality of good and bad set by a creator. There was discussion within natural rights, and even fundamental positive rights as to the breadth of this objective reality, but there was a consensus as a newly formed political society desired to achieve the common societal good as a higher priority over the rights of individuals, as long as the persons who were being governed consented. Thereby, believing that morality is objective, means that what is correct or good for people is fixed, and established; and any attempts to deviate from what is good will cause destruction; this view tends to be more closed-minded but also higher in consciousness.

Whereas believing that morality is relative, requires a religious zealousness to concepts such as freedom and equality as “Rousseau said a civil religion is necessary to society, and the legislator has to appear draped in the colors or religion.”[69] Meaning that the downstream terms like culture that are meant to preserve a religious like structure while combining reason and religion without drawing the distinction between their polarities.[70] The fundamental issue with relative morality then is that it asserts that there are values or fundamental principles such as freedom and equality but it does not search for or explain the origin of these principles and there is no expedition of determining good and evil just merely asserting so. Further, since nature of people is not stagnant and is not fixed, it is something that society can move past; however, no evidence is required to back up this assumption, the only assumption necessary is believing that you are a moral and just being.[71] Even if there is no standard by which this justness can be substantiated since “secularism is the wonderful mechanism by which religion becomes nonreligion.”[72]

From a practical level, the issue with people who push for relative morality and the individual rights that are subsequently asserted, is that these values are not authentic. Freedom and equality are vague principles that are based on nature, nor are they negotiated with people groups are working together because they have shared “values by which a life can be lived.”[73] Such true values must compass lessons, stories, and teachers who live by example of how day-to-day life should be conducted, such a Moses, Jesus, Homer, Buddha, “as a value is only a value if it is life-preserving and life-enhancing” for the people who live by said value.[74] Such as respect for life, treating others as you would want to be treated, giving charity, attending community events.

Egalitarianism is founded on rationality, but egalitarian values are not based on the nature of those who it would force to conform to egalitarianism.[75] Thereby, this secular idea of egalitarianism imposes positive rights that individuals have, based on the devout belief that everything being equal is inherently good, but provides no supporting evidence from the nature of the individuals who are claimed to need the rights. This view then can dismantle the idea of the common good, since the common good does not hold or believe that freedom or equality trump the nature of individuals. Relative morality is fluid and leads to openness, but this openness is confined to mandating the belief of Egalitarianism which promotes indifference to how others are conducting themselves. Whereas, for there to be a consensus as to what constitutes the common good, there must be a shared sense of fundamental beliefs that does not hold all people equal, whether that be in physical ability, mental capacity, or some other criteria.

Those who are in the moral relativism camp, appear to be more in the Lockean camp of believing that by nature people are moral. But they twist Locke’s words of a social contract and individual rights to Egalitarianism at the expense of the common good. The moral relativist end fulfills Madison’s deepest fears and uses their religious tiered principles of freedom and equality to subvert the common good by fractioning the interests of the minorities groups as being in the opposition to the majority. Further, they completely misinterpret the criticism that the founders had of a Majority, the criticism was of a democracy that used popularity to subvert the common good, not of Majority merely using their political powers for not Egalitarian uses. Also, they overlook that the principles of freedom and equality requires a repression of nature by reconstructing what it is to be human.[76] For a moral objectivist there is assumed to be a nature that exists and we freely subject ourselves to a social contract that seeks to elevate the negative inclinations of nature. While a moral relativist believes that nature has been conquered and now, we merely need to reorder our social contract as to reflect the proper forms of social conditions that are fully within our control, by placing equality and freedom as the foundations of our political society. In this endeavor, these political principles have destroyed the religious faith and traditional morality by advocating for individual rights that exist without any form of responsibility.

- Delineation: Natural Rights, Fundamental Positive Rights, and Ordinary Positive Rights.

For the founding Fathers rights were:

“Divided between natural rights, which were liberties that people could exercise without governmental intervention, and positive rights, which were legal privileges or immunities defined in terms of governmental action or inaction, like the rights of due process, habeas corpus, and confrontation.” (“Yale Law Journal – Natural Rights and the First Amendment”)[77]

The fundamental positive rights appear easy to delineate as they are the ones in the Bill of Rights. As for natural rights, being that are not legally or definitionally recognized, they are derived from life-preserving and life-enhancing values, in which there would reasonable be disagreement because one’s tradition, belief system, religious faith or denomination. Examples of Natural rights consisted of rights that did not depend on the government, such as speaking, eating or walking.[78] Ordinary positive rights were meant to be laws that were believed to be in the common good of the political society.

- My Take Aways on Rights

When I started my research into the topic of rights, I started with the assumption of referring to natural rights and fundamental rights together as negative rights and I was referring to ordinary positive rights as positive rights. However, after conducting the research that went into this essay, I have realized that there is a more fundamental issue at play. The use of egalitarian principles being utilized to subvert the United States political cohesion into factions that are fighting over pieces of the pie for their own group’s interests, instead of the interest of the common good.

My prior criticism of assertions regarding the right to healthcare, or a right to food, was that the political society we live in is not mandated to force the Federal[79] or State[80] government to take action when a citizens personal liberties, or fundamental positive rights, have been infringed upon by a fellow citizen. Further, only in special situations does current law require of State acters to act:

Only in certain limited circumstances does the Constitution impose affirmative duties of care on the states.[81] As originally defined by the Supreme Court, those circumstances exist where (1) the state takes a person into custody, confining the person against his or her will, and (2) the state creates the danger or renders a person more vulnerable to an existing danger.[82] However, the “stated-created danger” doctrine has since been superceded by the standard employed by the Supreme Court in Collins.[83] Now, “conduct by a government actor will rise to the level of a substantive due process violation only if the act can be characterized as arbitrary or conscience shocking in a constitutional sense.”[84][85]

However, now my criticism comes from the fact that these alleged rights are purely egalitarian principles that are asserting an alleged right while masquerading as a public common good. This façade wears the mask of rationality, and emotional manipulation, to benefit certain groups at the cost of a cohesive nation that wants a unified common good. The nature of the egalitarian gamesmanship is to find minorities and persons of different identities and pit them against the Majority who is claimed to be holding unequal power, rank, or influence.

These would be rights are merely tools of the secular religious dogma that is not based on how individuals live their lives but claims to be the champion of the individuals’ rights at the expense of community, and the common good that individuals would normal coalesce around and work together to achieve. Instead, the concepts of freedom and equality replace the common good with the personal interest of retaining the ability to rebel against the common good for the sake of one’s own alleged good.

There are arguments that a right such as a right to healthcare is a natural right, but it is obvious that when someone says this, they are not using Natural right in the same way that it was being articulated in the Founding-Era. Once there was a Political Society, or a government that agreed to come together, the common good was the main goal of the political society, not the individual.

History to the egalitarian appears to be a source of explaining why they deserve more individual rights or why they deserve reparations. There appears to be no thought of the common good as separable from what the person wants in the moment. “To live for the moment is the prevailing passion—to live for yourself, not for your predecessors or posterity. We are fast losing the sense of historical continuity, the sense of belonging to a succession of generations originating in the past and stretching into the future.”[86]

[1] Natural v. Legal; Claim v. Liberty; Individual v. Group; Civil, political, economic, social, religious, cultural… etc.

[2] Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan. Edited by Edwin Curley. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1994. Chapter 5.

[3] such as Institutional racism as a philosophy that hinges on whiteness and white people with power as being the new definition of racism. Where because white or straight people are the majority by egalitarian standards other groups or minorities need to be make equal to the majority. Even if it makes no sense or is judged by a moving standard.

[4] Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Rectitude. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/rectitude

[5] Harper, D. (n.d.). Right. In Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.etymonline.com/word/right

[6] Oxford English Dictionary. (n.d.). Right, adj. In Oxford English Dictionary Online. Retrieved from https://www.oed.com/dictionary/right_adj?tab=etymology#25350159

[7] 1 Rodney A. Smolla, Smolla and Nimmer on Freedom of Speech § 1:11 (2016).

[8] National Constitution Center. (n.d.). The Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. Retrieved from https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/white-papers/the-declaration-the-constitution-and-the-bill-of-rights

[9] Campbell, J. (2017). Republicanism and Natural Rights at the Founding. Constitutional Commentary, pg. 87. University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository.

[10] Wilson, J. F. (2011). The Founding Era (1774–1797) and the Constitutional Provision for Religion. In Oxford Handbooks Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195326246.003.0001

[11] Campbell, J. (2017). Republicanism and Natural Rights at the Founding. Constitutional Commentary, pg. 87. University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository.

[12] Id 88.

[13] Id 90, 112.

[14] Id 91.

[15] Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan. Edited by Edwin Curley. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1994. Chapter 6, 8, and 17. (Hobbes discusses the concept of the social contract and the formation of a commonwealth in Chapter XIII, titled “Of the Natural Condition of Mankind as Concerning their Felicity, and Misery,” and Chapter XVII, titled “Of the Causes, Generation, and Definition of a Commonwealth.” In Chapter VI, “Of the Interiour Beginnings of Voluntary Motions, Commonly Called the Passions; and the Speeches by which They are Expressed,” Hobbes discusses reason as a faculty guiding human actions and passions)

[16] Id Chapter 13.

[17] Id Chapters 17 and 18.

[18] Id chapter 17; Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (n.d.). Social Contract Theory. Retrieved from https://iep.utm.edu/soc-cont/#SH2a

[19]Locke, J. (1690). Second Treatise of Government (Chapter 2, Sections 6-8). Retrieved from https://english.hku.hk/staff/kjohnson/PDF/LockeJohnSECONDTREATISE1690.pdf

[20] Id Chapter 9 section 124

[21] ID Section 87

[22] Id Section 22, Chapter 8 section 95, chapter 4, and Chapter 13 section 149.

[23] Library of Congress. (n.d.). Thomas Jefferson: Declaration of Independence: Right to Institute New Government. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html

[24] Southern Methodist University. (n.d.). Influences on Madison’s Memorial and Remonstrance. Retrieved from https://people.smu.edu/religionandfoundingusa/james-madisons-memorial-and-remonstrance/influences-on-madisons-memorial-and-remonstrance/

[25] Pursuit of Happiness Foundation. (n.d.). John Locke. Retrieved from https://www.pursuit-of-happiness.org/history-of-happiness/john-locke/

[26]Library of Congress. (n.d.). Jefferson’s Draft of the Declaration of Independence. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/18.html

[27] Founders Online. (n.d.). James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, 24 October 1787. Retrieved from https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-08-02-0163

[28] Southern Methodist University. (n.d.). Influences on Madison’s Memorial and Remonstrance. Retrieved from https://people.smu.edu/religionandfoundingusa/james-madisons-memorial-and-remonstrance/influences-on-madisons-memorial-and-remonstrance/

[29] Isaac Kramnick, Republican Revisionism Revisited, 87 AM. HIST. REV. 629, 629–35 (1982) (surveying how a generation of “republican” scholarship downplayed the influence of Lockean ideas at the Founding).

[30] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (n.d.). Locke’s Influence. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/locke/influence.html

[31] Jeffrey Sikkenga, Lest We Forget: Clarence Thomas and the Meaning of the Constitution, 6 ON PRINCIPLE (Dec. 1998), available at http://www.ashbrook.org/publicat/onprin/v6n6/sikkenga. html (last visited Oct. 8, 2009). (Fortunately, though, the natural law approach has held a high place in American jurisprudence. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison agreed, for example, that the best guide to the Constitution is the Declaration of Independence and its philosophy of natural rights. This view was common at the Founding; so common, in fact, that early Supreme Court decisions, like Calder v. Bull (1798), claimed that even laws “not expressly restrained by the Constitution” should be struck down if they violate natural rights. Nor was this view limited to the Founding era. Before and during the Civil War, for example, Abraham Lincoln repeatedly appealed to the legal authority of the Declaration in his fight against slavery). See also discussion of William R. Long, Calder v. Bull (1798): The Issue of Natural Law (2005), available at http://www.drbilllong.com/LegalEssays/CalderlI.html (last visited Mar. 29, 2008).

[32] Influence of the Natural Law Theology of the Declaration of Influence of the Natural Law Theology of the Declaration of Independence on the Establishment of Personhood in the United Independence on the Establishment of Personhood in the United States Constitution H. Wayne House

[33] O’Scannlain, D. F. (2011). The Natural Law in the American Tradition (pp. 1516).

[34] Balkin, J. M., & Levinson, S. (Year of publication). To Alter or Abolish. USC Law Review, 416.

[35] Philip A. Hamburger, Natural Rights, Natural Law, and American Constitutions, 102 Yale L.J. 907, 908-911 (1993)

[36] See previous 4 footnotes. Social Contract Theory in American Case Law Social Contract Theory in American Case Law Anita L. Allen.

[37] Conley, Patrick T. (1992). The Bill of Rights and the States: The Colonial and Revolutionary Origins of American Liberties. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 109. ISBN 9780945612292.

[38] “Zephaniah Swift’s First Legal Texts in America”. Connecticut Judicial Branch Law Libraries. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

[39] Campbell, J. (2017). Republicanism and Natural Rights at the Founding. Constitutional Commentary, pg. 91. University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository.

[40] Id 92

[41] Id

[42]Campbell page 88 note 16 James Wilson, Of Municipal Law, in 1 COLLECTED WORKS OF JAMES WILSON 549, 553–54 (Kermit L. Hall & Mark David Hall eds., 2007); see also JOHN LOCKE, TWO TREATISES OF GOVERNMENT, bk. 2, chap. 9, § 130 (5th ed.; London, A. Bettesworth 1728) (individuals surrender “as much . . . natural Liberty . . . as the Good, Prosperity, and Safety of the Society shall require”).

[43] Campbel page 88 note 17 JOHN ADAMS, A DEFENCE OF THE CONSTITUTIONS OF GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 6 (Philadelphia, Hall & Sellers 1787); Alexander Hamilton, The Farmer Refuted (Feb. 23, 1775), in 1 THE PAPERS OF ALEXANDER HAMILTON 81, 88 (Harold C. Syrett ed., 1961).

[44] A founding father and former SCOTUS justice

[45] See, e.g., James Wilson, Considerations on the Nature, and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament (1774), in 1 COLLECTED WORKS OF JAMES WILSON, supra note 16, at 3, 5 n.c. (“The right of sovereignty is that of commanding finally—but in order to procure real felicity; for if this end is not obtained, sovereignty ceases to be a legitimate authority.”).

[46] Article I, Section 8, Clause 1: “The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;”

[47] Id Campbell ANNALS OF CONG. 1169 (Feb. 10, 1790) (remarks of Rep. Theodore Sedgwick).

[48] THE FEDERALIST NO. 84, supra note 45, at 578 (Alexander Hamilton). 54. See, e.g., Remarker, INDEP. CHRONICLE, Dec. 27, 1787, in 5 THE DOCUMENTARY HISTORY OF THE RATIFICATION OF THE CONSTITUTION 527, 529 (John P. Kaminski & Gaspare J. Saladino eds., 1998); Virginia Ratification Convention Debates (June 16, 1788) (remarks of George Nicholas), in 10 DOCUMENTARY HISTORY, supra note 32, at 1334.

[49] ID

[50] Campbell, J. (2017). Republicanism and Natural Rights at the Founding. Constitutional Commentary, pg. 96. University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository.

[51] Id 97

[52] Very great historical analysis but to esoteric for this essay.

[53] Campbell, J. (2017). Republicanism and Natural Rights at the Founding. Constitutional Commentary, pg. 103. University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository.

[54] Id 104

[55] Madison, J. (1787, April). Vices of the Political System of the United States, section 11. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-09-02-0187#:~:text=Among%20the%20vices%20of%20the,over%20commerce%3B%20and%20in%20general

[56] Id

[57] Id

[58] James L. Hutson, Virtue Besieged: Virtue, Equality, and the General Welfare in the Tariff Debates of the 1820s, 14 J. EARLY REP. 523, 525 (1994).

[59] Nussbaum, Martha C. (2012). Philosophical Interventions: Reviews 1986–2011. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199777853.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-977785-3. Pg 45 (Nussbaum questions if Allan Bloom is really a philosopher).

[60] Dworkin, R. (n.d.). pg. 82 Taking Rights Seriously. Retrieved from https://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/Ronald%20Dworkin%20-%20Hard%20Cases.pdf

[61] Id.

[62] Id.

[63] Id 83.

[64] The Heritage Foundation. (n.d.). Justice as Fairness (p. 43). Retrieved from https://www.heritage.org/progressivism/report/the-hidden-influence-john-rawls-the-american-mind ((1) Everyone is entitled to the same basic liberties, and (2) Inequalities in social or economic outcomes are only justifiable if: (a) All citizens have a fair shot at attaining the offices and positions from which these inequalities result, and (b)They benefit the most disadvantaged members of society)

[65] Rawls, J. (1971). A Theory of Justice (p. 4).

[66] Dworkin, R. (1977). Taking Rights Seriously (p. xi); Sowell, T. (1996). The Vision of the Anointed (pp. 209-211).

[67] Queiroz, R. (2018). Individual liberty and the importance of the concept of the people. Palgrave Communications, 4, 99. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0151-3

[68] Quintavalla, A., & Heine, K. (2019). Priorities and human rights. The International Journal of Human Rights, 23(4), 679–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2018.1562917

[69] Bloom, A. (1988). The Closing of the American Mind (p. 196). New York: Simon and Schuster.

[70] Id 197

[71] Id 199

[72] Id 211

[73] Id 201

[74] id

[75] id

[76] Id 97

[77] https://www.yalelawjournal.org/article/natural-rights-and-the-first-amendment citing See Congressional Debates (June 8, 1789) (statement of Rep. James Madison), in 11 Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America 811, 822 (Charlene Bangs Bickford et al. eds., 1992) [hereinafter Documentary History of the First Federal Congress]; Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Noah Webster, Jr. (Dec. 4, 1790), in 18 The Papers of Thomas Jefferson 131, 132 (Julian P. Boyd ed., 1971); An Old Whig IV, Index. Gazetteer (Philadelphia), Oct. 27, 1787, reprinted in 13 The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution 497, 501 (John P. Kaminski & Gaspare J. Saladino eds., 1981) [hereinafter Documentary History of the Ratification]. The Founders sometimes referred to positive rights as adventitious rights or social rights. See The Impartial Examiner 1, Va. Index. Chron. (Richmond), Feb. 20, 1788, reprinted in 8 Documentary History of the Ratification, supra, at 387, 390 (1988); [George Logan], Letters Addressed to the Yeomanry of the United States . . . 39 (Philadelphia, Eleazer Oswald 1791); Philanthropos, Newport Herald, June 17, 1790, reprinted in 26 Documentary History of the Ratification, supra, at 1051, 1051 (John P. Kaminski et al. eds., 2013).

[78] ID.

[79] Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife: 504 U.S. 555 (1992)

[80] 42 USCS § 1983

[81] Doe v. Braddy, 673 F.3d 1313, 1318 (11th Cir. 2012).

[82] DeShaney v. Winnebago Cnty. Dep’t of Soc. Servs., 489 U.S. 189, 198-201, 109 S. Ct. 998, 103 L. Ed. 2d 249 (1989).

[83] Waddell v. Hemerson, 329 F.3d 1300, 1305 (11th Cir. 2003).

[84] Id. (citing Collins, 503 U.S. at 128).

[85] McKenzie v. Talladega City Bd. of Educ., 242 F. Supp. 3d 1244, 1255-56.

[86] Lasch, C. (1991). The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (p. 5).